Members of the Neuromechanics and Mobility Lab had a busy week attending the 2025 Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America (RESNA) Conference, held as part of RehabWeek 2025 from May 12-16 in Chicago, IL.

RehabWeek is a premier, week-long event that brings together multiple conferences in the field of rehabilitation technology. It fosters cross-disciplinary collaboration and innovation among researchers, clinicians, and industry professionals. Our lab was proud to be part of this vibrant community, with several members presenting their research and contributing to the ongoing dialogue on the future of rehabilitation science.

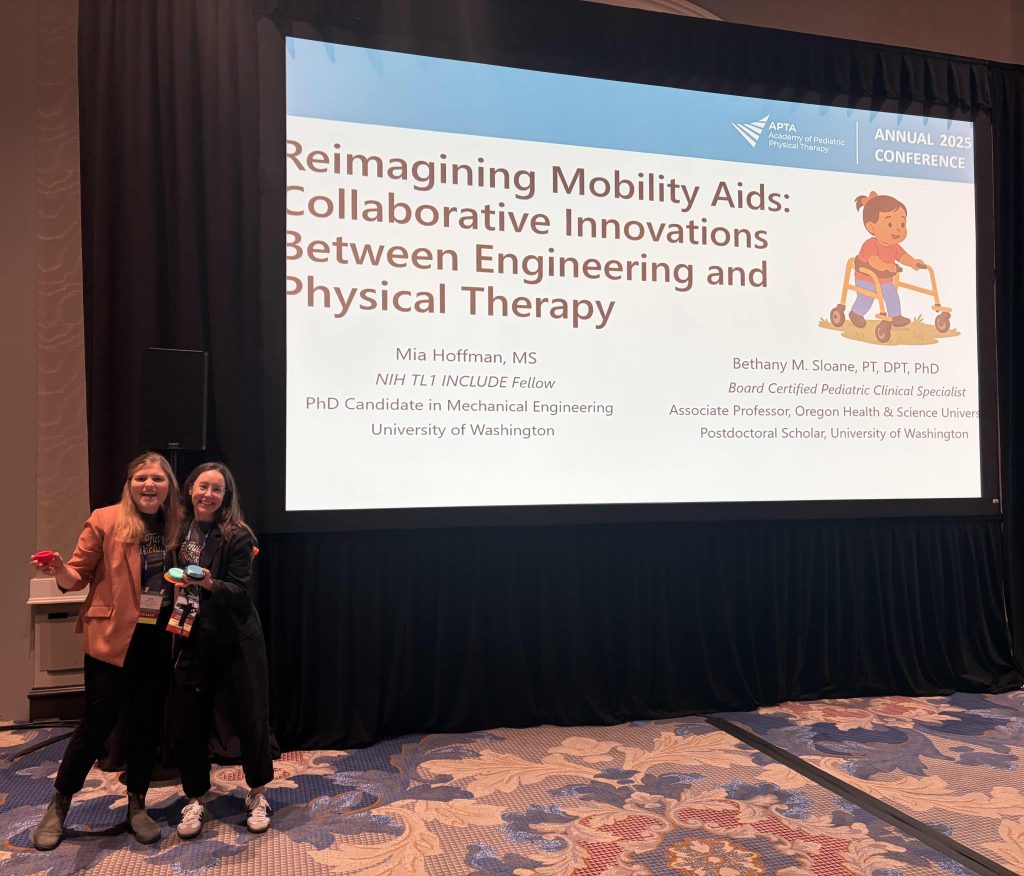

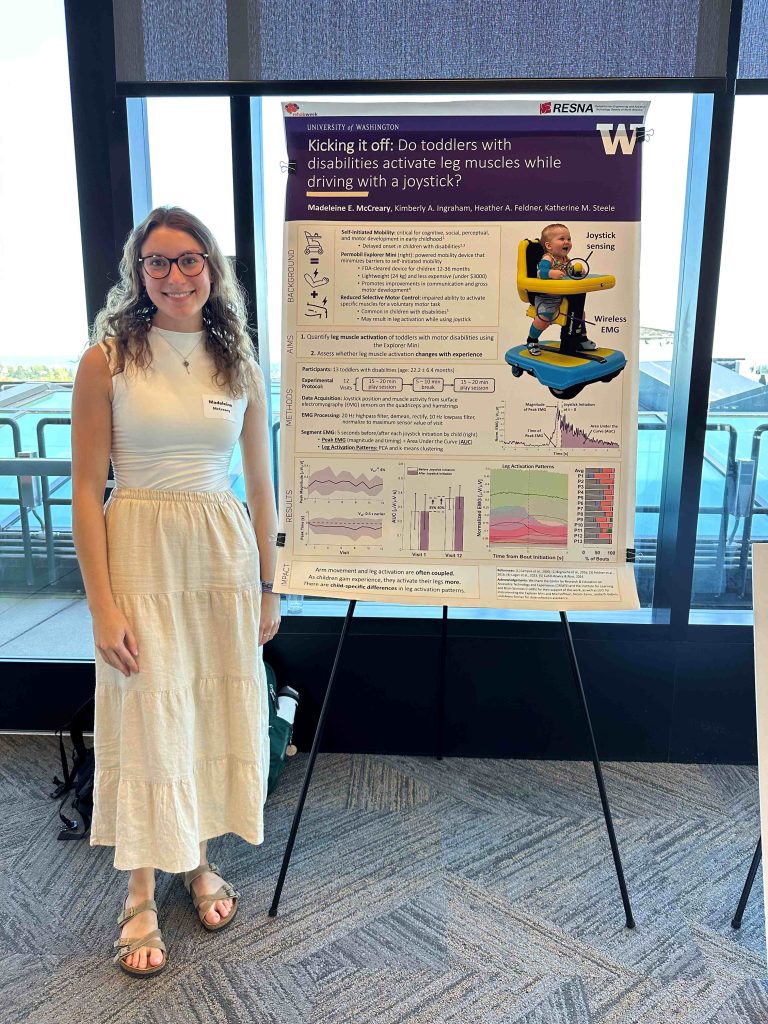

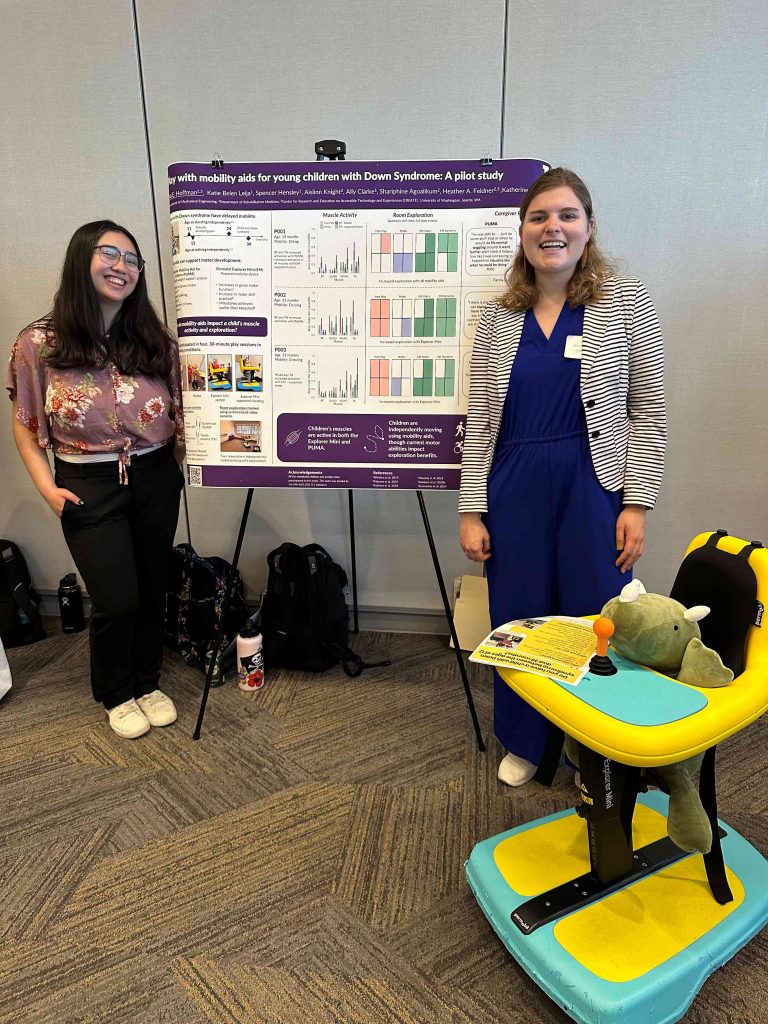

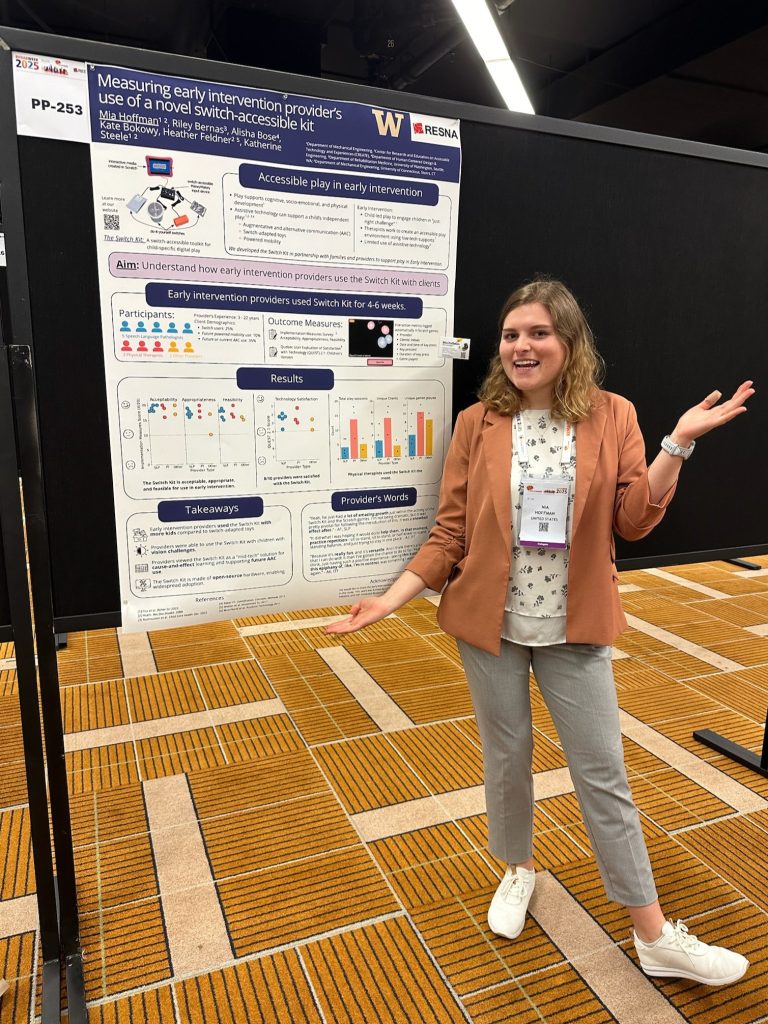

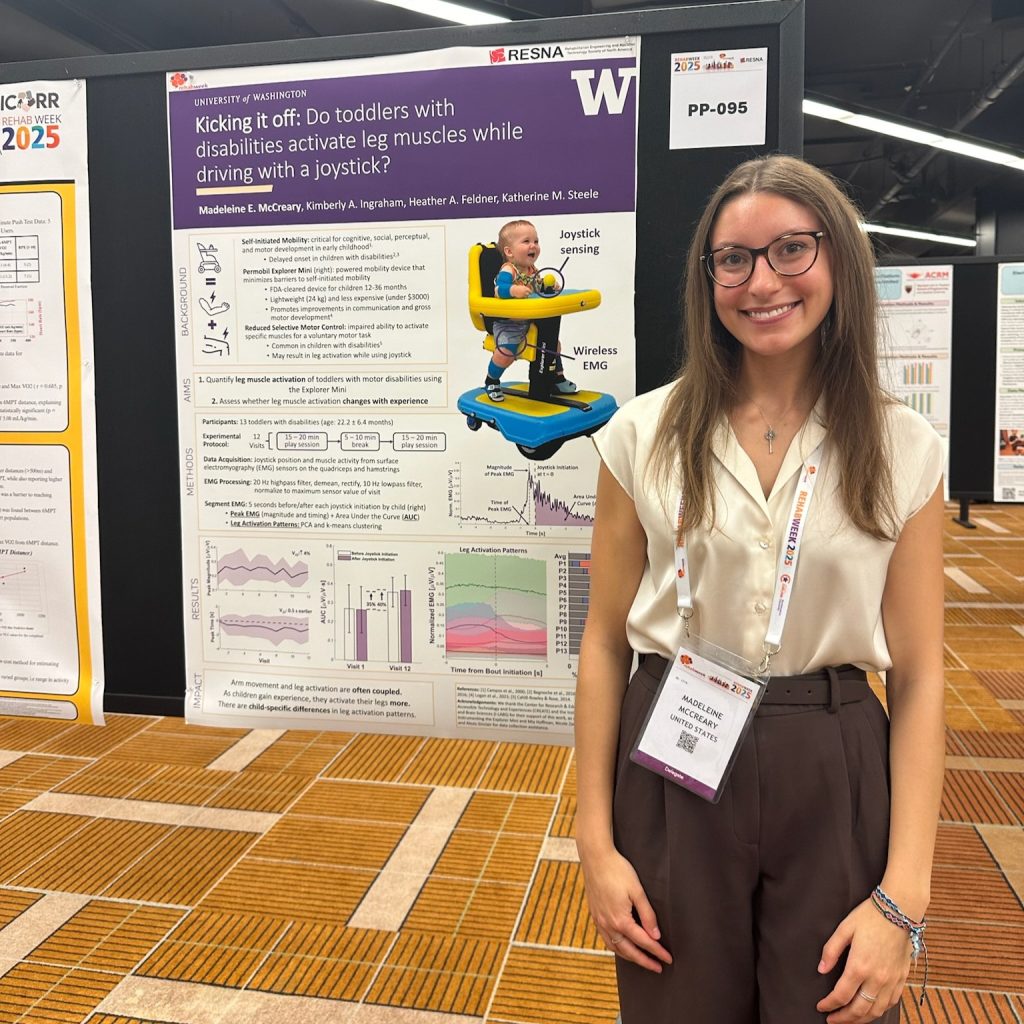

Two of our PhD students, Mia Hoffman and Madeleine McCreary, participated in the RESNA Student Scientific Paper Competition and presented their work during the Student Scientific Paper Platform session. Mia presented her research titled “Measuring Early Intervention Providers’ Use of a Novel Switch-Accessible Play Kit,” while Maddie shared findings from our lab’s Early Mobility & Play research in her talk, “Kicking it off: Do toddlers with disabilities activate leg muscles when driving with a joystick?”

Mia Hoffman also led a session on Play and Recreation in Assistive Technology titled “Switch It Up: From Adapted Toys to Therapeutic Gaming.”

Alexandra (Sasha) Portnova-Fahreeva presented a poster titled “Evaluating the Effects of Noninvasive Spinal Stimulation on Gait Parameters in Cerebral Palsy via Markerless Motion Capture” sharing findings from our lab’s Spinal Neuromodulation research. She also participated in the RESNA Student Design Challenge with her project, “H.A.T. – A Camera-Based Finger Range-of-Motion Hand Assessment Tool to Enhance Therapy Practices” where she and her team received honorable mention.

Katie Landwehr-Prakel presented a poster on “Cardiovascular Load of Using a Walker-Based Exoskeleton in Children with Cerebral Palsy,” and placed in the top 10 of the Fast Forward Poster Competition.

We are especially proud to share that Mia Hoffman was awarded 1st place and Madeleine McCreary received 2nd place in the Student Scientific Paper Competition. Congratulations to both for their outstanding work and well-deserved recognition.

We’re incredibly proud of our team’s contributions and accomplishments at RehabWeek 2025!