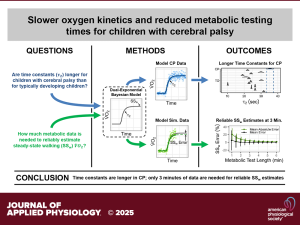

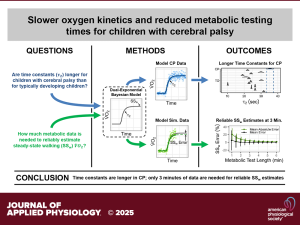

Journal Article in Journal of Applied Physiology

Prior research using indirect calorimetry has shown that children with cerebral palsy (CP) exhibit significantly increased energetic costs during walking. However, metabolic testing to obtain oxygen cost is challenging. As a result, differences in oxygen uptake kinetics (V̇o2) in CP compared with their typically developing peers remain unexplored. Step changes in work rate have been shown to result in an exponential V̇o2 response with three distinct phases 1) cardiodynamic, 2) primary, and 3) steady-state.

Aim: This study aimed to apply a dual-exponential Bayesian model to assess the time constant of the primary phase V̇o2 response from resting to walking in children with CP. In addition, evaluate the model’s ability to estimate steady-state V̇o2 using shorter test durations.

Aim: This study aimed to apply a dual-exponential Bayesian model to assess the time constant of the primary phase V̇o2 response from resting to walking in children with CP. In addition, evaluate the model’s ability to estimate steady-state V̇o2 using shorter test durations.

Methods: A dual-exponential Bayesian model was applied to metabolic data from a sample of 263 children with CP. The model estimated the time constant of the primary phase V̇o₂ response and tested the accuracy of steady-state V̇o₂ estimation using only the first 3 minutes of data, compared to the standard 6-minute duration.

Results: The median V̇o2 time constant was 33.1 s (5th–95th percentile range: 14.5–69.8 s), significantly longer than reported values for typically developing children (range of means: 10.2–31.6 s). Furthermore, the model accurately estimated steady-state V̇o2 using only the first 3 min of metabolic data compared with the typical 6 min used in current clinical practice. The 3-min estimate explained >95% of the 6-min estimate variance, with <5% mean absolute error.

Interpretation: Slower oxygen kinetics in children with CP suggest impairments in metabolic control, potentially contributing to their higher energy demands. Although the exact mechanisms remain unclear, this study provides valuable insights into the walking energetics of children with CP and presents a more efficient method for analyzing V̇o2 for this population.