Journal Article in Journal of Biomechanics:

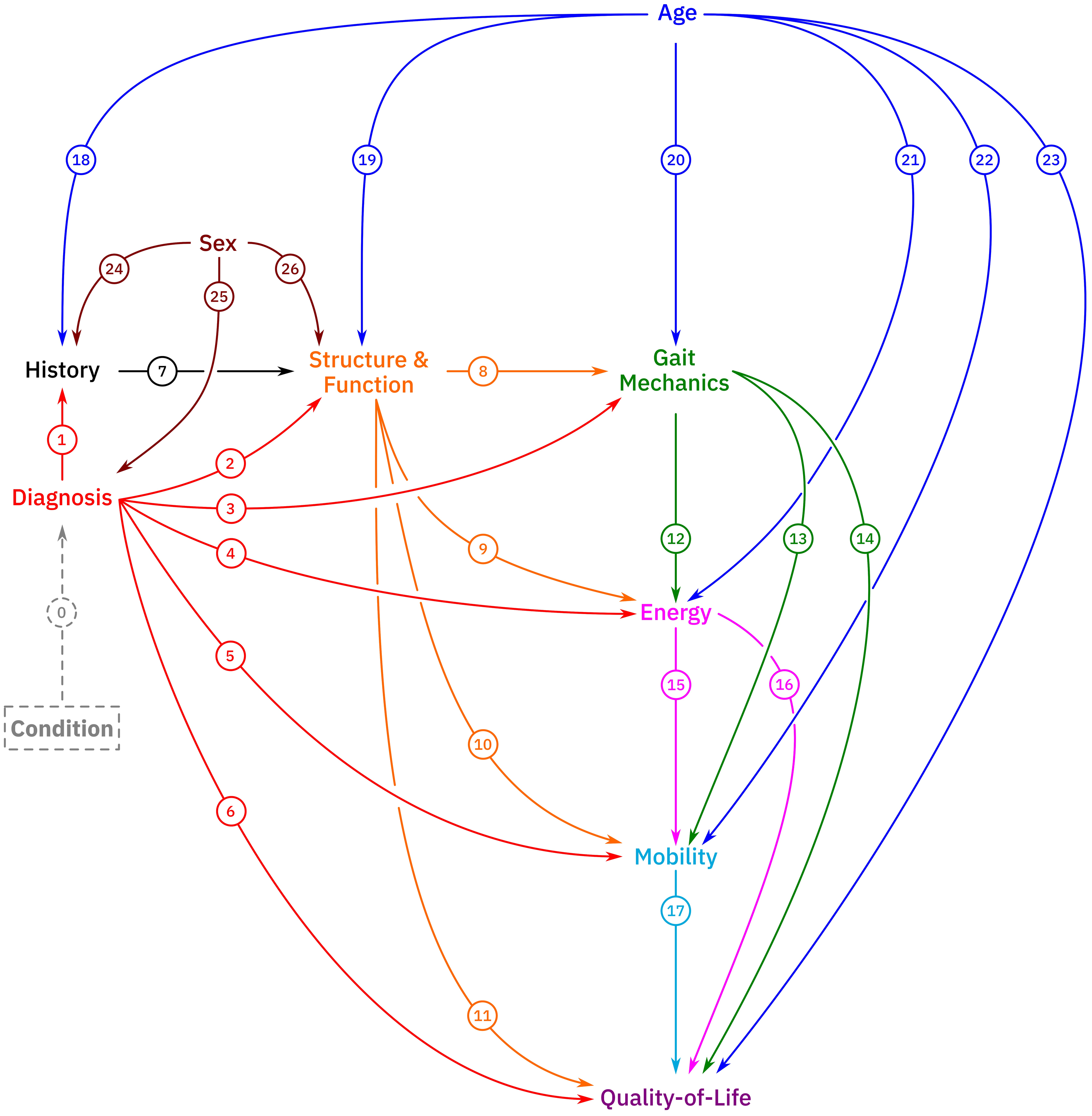

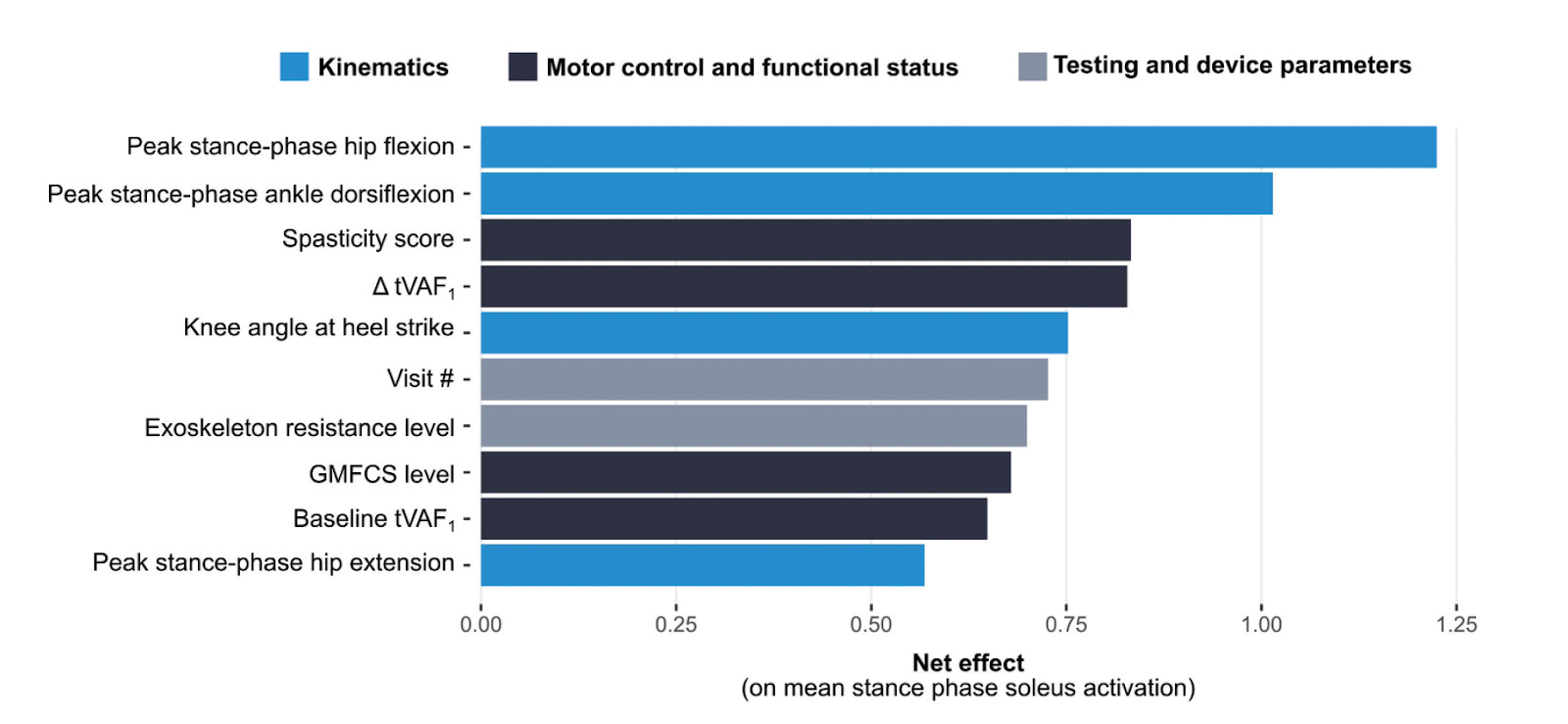

Physiological and biomechanical responses to mechanical assistance from wearable technology are highly variable, especially for clinical populations; tools to predict how users respond to different types of exoskeleton assistance may optimize the prescription process and uncover underlying mechanisms driving locomotor changes in the context of personalized wearable/assistive technology.

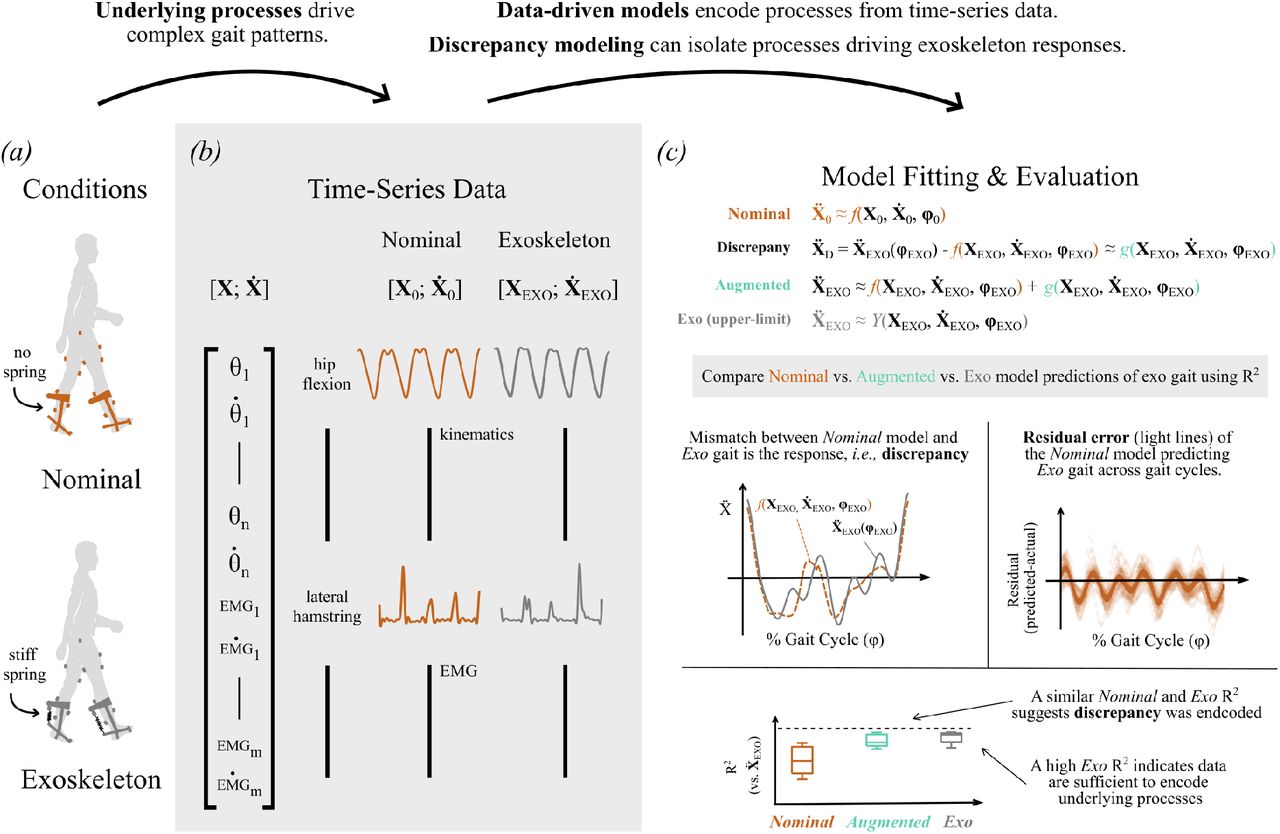

Aim: The purpose of this study was to determine if a discrepancy modeling framework could quantify individual-specific gait responses to ankle exoskeletons.

Method: We employ a machine learning technique — neural network based discrepancy modeling — on gait data from 12 non-disabled adults to capture within-participant differences in walking dynamics without vs. with a bilateral passive elastic ankle exoskeletons applying 5 N-m/deg of torque. We fit three models: Nominal gait (no exo), Exo, and Discrepancy. Then, post-fitting, we extend the Nominal by the Discrepancy Model (Augmented). We hypothesize that if Augmented (Nom+Discrep) can capture similar amount of variability as the Exo model, then it can be inferred that the discrepancy model accurately captures how a user will respond to an exoskeleton — without direct information about that user’s physiology or motor coordination.

Results:While joint kinematics during Exo gait were well predicted using the Nominal model (median 𝑅2 = 0.863 − 0.939), the Augmented model significantly increased variance accounted for (𝑝 < 0.042, median 𝑅2 = 0.928 − 0.963). For EMG, the Augmented model (median 𝑅2 = 0.665 −

0.788) accounted for significantly more variance than the Nominal model (median 𝑅2 = 0.516 − 0.664). Minimal kinematic variance was left unexplained by the Exo model (median 𝑅2 = 0.954 − 0.978), but only accounted for 72.4%–81.5% of the median variance in EMG during Exo gait across all individuals.

Interpretation:Discrepancy modeling successfully quantified individuals’ exoskeleton responses without requiring knowledge about physiological structure or motor control. However, additional measurement modalities and/or improved resolution are needed to characterize Exo gait, as the discrepancy may not comprehensively capture response due to unexplained variance in Exo gait.