Journal Article in Prosthetics and Orthotics International:

This research provides insights into the lived experiences of individuals with CP and their caregivers regarding the process of obtaining and using an AFO. Further opportunities exist to support function and participation of people with CP by streamlining AFO provision processes, creating educational materials, and improving AFO design for comfort and ease of use.

Aim: The study objective was to evaluate the lived experiences of individuals with CP and their caregivers regarding AFO access, use, and priorities. We examined experiences around the perceived purpose of AFOs, provision process, current barriers to use, and ideas for future AFO design.

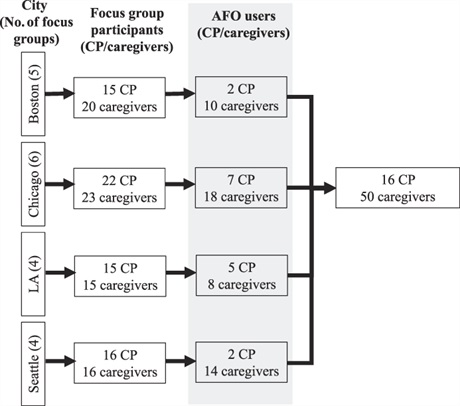

Method: Secondary data analysis was performed on semistructured focus groups that included 68 individuals with CP and 74 caregivers. Of the focus group participants, 66 mentioned AFOs (16 individuals with CP and 50 caregivers). De-identified transcripts were analyzed using inductive coding, and the codes were consolidated into themes.

Results: Four themes emerged: 1) AFO provision is a confusing and lengthy process, 2) participants want more information during AFO provision, 3) AFOs are uncomfortable and difficult to use, and 4) AFOs can benefit mobility and independence. Caregivers and individuals with CP recommended ideas such as 3D printing orthoses and education for caregivers on design choices to improve AFO design and provision.

Interpretation: Individuals with CP and their caregivers found the AFO provision process frustrating but highlight that AFOs support mobility and participation. Further opportunities exist to support function and participation of people with CP by streamlining AFO provision processes, creating educational materials, and improving AFO design for comfort and ease of use.