Journal Article in Journal of Biomechanics

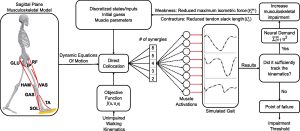

Muscle activity during gait can be described by a small set of synergies, weighted groups of muscles, that are theorized to reflect underlying neural control. For people with neurologic injuries, like cerebral palsy or stroke, even fewer synergies are required to explain muscle activity during gait. This reduction in synergies is thought to reflect altered control and is associated with impairment severity and treatment outcomes. Individuals with neurologic injuries also develop secondary musculoskeletal impairments, like weakness or contracture, that can impact gait. Yet, the combined impacts of altered control and musculoskeletal impairments on gait remains unclear.

Aim: In this study, we use a two-dimensional musculoskeletal model constrained to synergy control to simulate unimpaired gait.

Aim: In this study, we use a two-dimensional musculoskeletal model constrained to synergy control to simulate unimpaired gait.

Methods: We vary the number of synergies, while simulating muscle weakness and contracture to examine how altered control impacts sensitivity to musculoskeletal impairment while tracking unimpaired gait.

Results: Results demonstrate that reducing the number of synergies increases sensitivity to weakness and contracture for specific muscle groups. For example, simulations using five-synergy control tolerated 40% and 51% more knee extensor weakness than those using four- or three-synergy control, respectively. Furthermore, when constrained to four- or three-synergy control, the model was increasingly sensitive to contracture and weakness of proximal muscles, such as the hamstring and hip flexors. Contrastingly, neither the amount of generalized nor plantarflexor weakness tolerated was affected by the number of synergies.

Interpretation: These findings highlight the interactions between altered control and musculoskeletal impairments, emphasizing the importance of measuring and incorporating both in future simulation and experimental studies.